In the annals of colonial history, the Mombasa–Nairobi Railway project stands as a monumental testament to human endeavor, engineering prowess, and the intersection of cultures. Yet, amidst the tales of colonial enterprise, one often overlooked narrative is that of the Indian diaspora, whose labor and ingenuity were pivotal in the realization of this ambitious endeavor. As we delve into the past, we uncover the indelible mark left by the Indian community on the development of East Africa during British colonial times.

Mombasa, situated along the coast of Kenya, holds immense historic significance as one of the oldest and most important port cities in East Africa. With a rich history dating back centuries, Mombasa has been a pivotal hub for trade, commerce, and cultural exchange along the Indian Ocean coast. Its strategic location made it a focal point for maritime routes connecting Africa with Asia and the Middle East, attracting traders, explorers, and settlers from around the world. Over the centuries, Mombasa has been influenced by various civilizations, including Arab, Persian, Portuguese, and British, each leaving a distinct imprint on its architecture, cuisine, and customs. Today, Mombasa continues to serve as a bustling maritime gateway, facilitating international trade and tourism while preserving its vibrant cultural heritage for future generations to appreciate.

Fort Jesus on Mombasa city of Indian Ocean and Fort Kampala on banks of Victoria Lake were two forts built between 1593 and 1596 by Portuguese for secure of the route to India discovered by Vasco De Gama.

The history of British trade with or from Mombasa, Kenya, is intertwined with the broader colonial expansion of the British Empire in East Africa. Mombasa's strategic location along the Indian Ocean coast made it a crucial center for maritime trade and a gateway to the interior of Africa. Kenyan school history books place the founding of Mombasa as 900 A.D. It must have been already a prosperous trading town in the 12th century, as the Arab geographer al-Idrisi mentions it in 1151. It came under the exploration and later control of the Omani Empire around the 14th and 15th centuries.

The British East India Company established its presence in Mombasa during the 19th century, primarily to secure trade routes to India and access the resources of the African interior - Kenya and Uganda. Initially, British trade with Mombasa focused on goods such as ivory, spices, and slaves, which were exchanged for manufactured goods from Britain and India. Mombasa served as a key trading post along the East African coast, facilitating commerce between British merchants, Arab traders, and local African communities.

In 1887, the British government formalized its control over Mombasa and the surrounding coastal areas through treaties and agreements with local rulers. This paved the way for the construction of the Mombasa–Nairobi Railway, a monumental project aimed at linking the Indian Ocean port of Mombasa with the interior of Kenya. The railway not only facilitated the transportation of goods and resources but also further cemented British influence in the region.

The construction of the railway posed numerous engineering challenges, including the need to navigate steep gradients, rocky outcrops, and swampy marshlands. Additionally, the project faced logistical hurdles such as disease outbreaks, shortage of labor, and attacks from local tribes resisting British colonization.

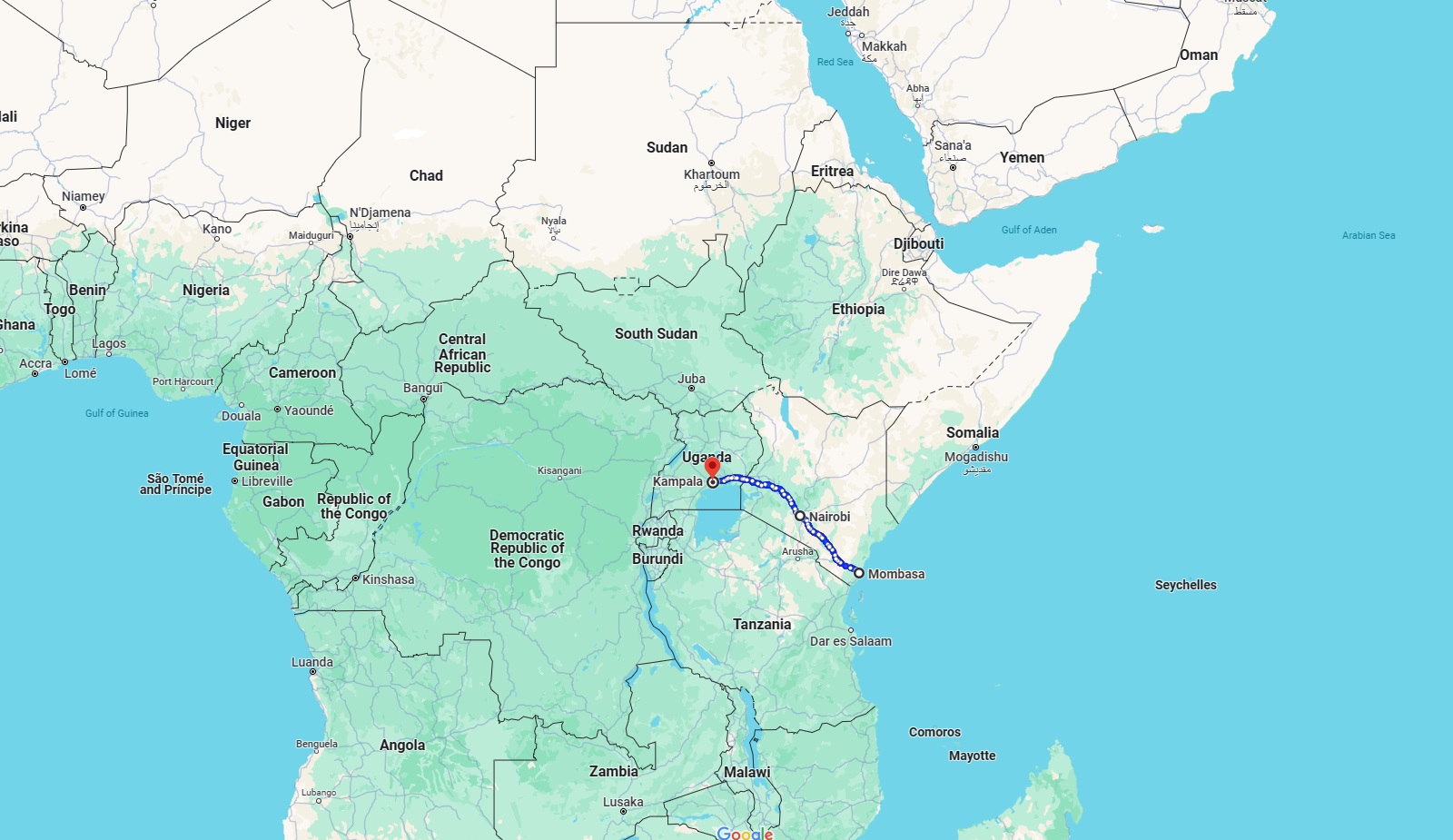

The railway line was nicknamed "Lunatic Line" due to the skepticism with which many viewed the ambitious endeavor. The sheer audacity of attempting to build a railway through such inhospitable terrain led some to dismiss the project as the product of madness or folly. However, despite the immense difficulties and setbacks, the Mombasa–Nairobi Railway was eventually completed in 1901, marking a significant milestone in colonial history and transforming the socio-economic landscape of East Africa. ‘Where it is going, nobody knows, what is the use of it, none can conjecture ... It is clearly nought but a lunatic line’- politician and arch-critic Henry Labouchere coined the term seeing it as hubris of imperial Britain to make it possible at the cost of many lives.

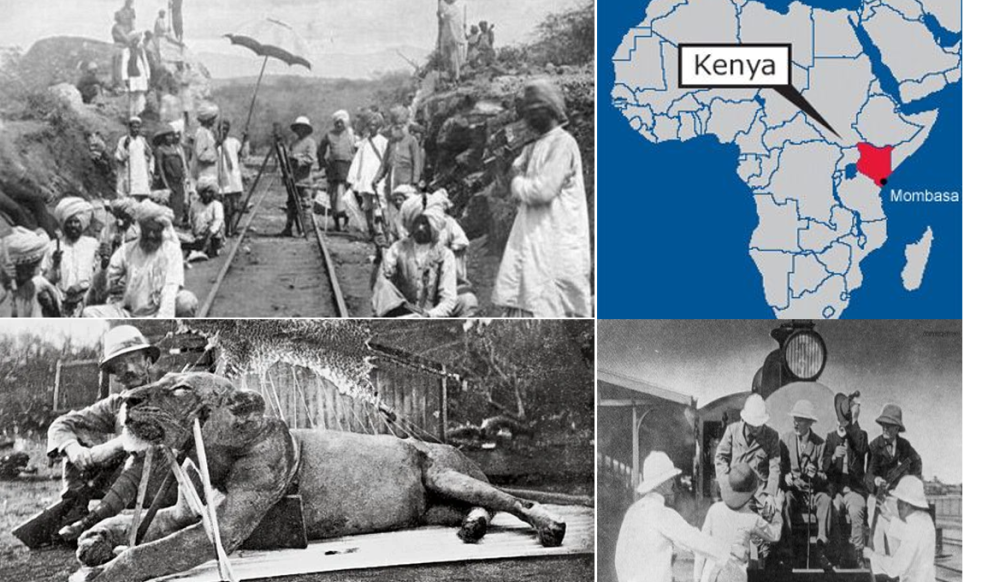

Enter the Indian diaspora. Drawn by the promise of employment and opportunity, thousands of Indian laborers, craftsmen, and engineers ventured across the Indian Ocean to participate in the construction of the railway. Hailing from diverse backgrounds and regions of the Indian subcontinent, they brought with them a wealth of skills and expertise that would prove indispensable in overcoming the formidable challenges that lay ahead.

This line was laid in Kenya by Indian labourers at the behest of the British, who desperately wanted to keep the advance of imperial Germany in Africa in check. The line employed 32,000 Indians, 6500 of them were left wounded by nature, African tribes, wild animals and of course the British imperial policies of which 2500 never came back to India. The 1460 miles, which become a 2350-kilometre railway line connecting the Mombasa coast of Indian Ocean in Kenya to Kampala, Uganda.

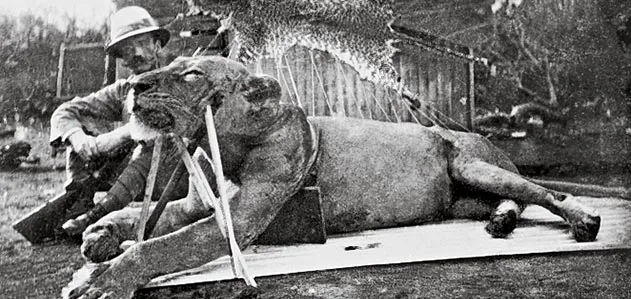

The daunting wildlife of Africa posted a constant challenge during the construction of this railway line. According to the memoirs written by British rail engineer Col JT Patterson ‘Man-Eaters of Tsavo’ the two man-eater lions preyed on somewhat 28 to 100 rail workers before being shot down. One story of Patterson’s Sikh Jemadar Ungan Singh who was dragged out by unseen spirit from his tent at night is enough to gauge the fear of the workers then. Only his head was found intact. The Tsavo Man-Eaters were a pair of large man-eating male lions in the Tsavo region of Kenya, which were responsible for the deaths of many construction workers on the Kenya-Uganda Railway between March and December 1898. The lion pair was said to have killed dozens of people, with some early estimates reaching over a hundred deaths. While the terrors of man-eating lions were not new in the British public perception, the Tsavo Man-Eaters became one of the most notorious instances of dangers posed to Indian and native African workers of the Uganda Railway.

The famine further made lives of the labourers miserably. An Indian merchant Alibhai Mulla Jeevanji who later changed the face of Nairobi as a city was given contact of arranging for the labour. He hired labour mostly from Punjab region and thus majority were Sikhs. After the construction started in May 1896, roughly 4000 Indians had come to Africa by 1897 and the British too had realised it’s not going to be easy.

The labor force comprised primarily of indentured workers, whose journey to East Africa was marked by hardship and exploitation. Yet, despite the harsh conditions and meager wages, they toiled tirelessly, enduring sweltering heat, disease, and the constant threat of accidents. Their resilience and determination were nothing short of remarkable, laying miles of track and carving through the unforgiving terrain with sheer grit and perseverance.

But it wasn't just the laborers who played a crucial role; Indian entrepreneurs and merchants also made significant contributions to the project. From supplying essential goods and services to providing financial support, they played a vital role in sustaining the railway's construction and operation. Moreover, Indian communities established along the railway route served as vital hubs of commerce and culture, contributing to the social and economic fabric of the region. Simultaneously, Indian engineers and craftsmen played a crucial role in the technical aspects of the project, employing their expertise in surveying, architecture, and construction to overcome the numerous engineering challenges posed by the East African landscape. Drawing on their knowledge of traditional building techniques and materials, they devised innovative solutions to problems ranging from bridging ravines to tunneling through mountains. Their contributions not only accelerated the pace of construction but also ensured the durability and safety of the railway infrastructure.

The Indian diaspora's legacy in the Mombasa–Nairobi Railway project endures as a testament to their resilience, resourcefulness, and enduring impact on East African history. Beyond the physical infrastructure they helped build, their presence left an indelible imprint on the cultural, social, and economic landscape of the region. Today, as we reflect on this shared history, it is essential to recognize and celebrate the contributions of the Indian community to the development and progress of East Africa. Their story serves as a poignant reminder of the complex interplay of power, identity, and agency in the colonial era, and the enduring legacy of those who shaped the world we inhabit today.

Today a vast majority of people among the Indian Diaspora in East Africa trace their roots back to the forefathers who built Africa and the Mombasa–Nairobi Railway Project.

521 Views

521 Views 1 comment

1 comment

Mar 29, 2024, 12:31 pm EDT

i never knew about this history...this is cool.